The Case for Co-Design

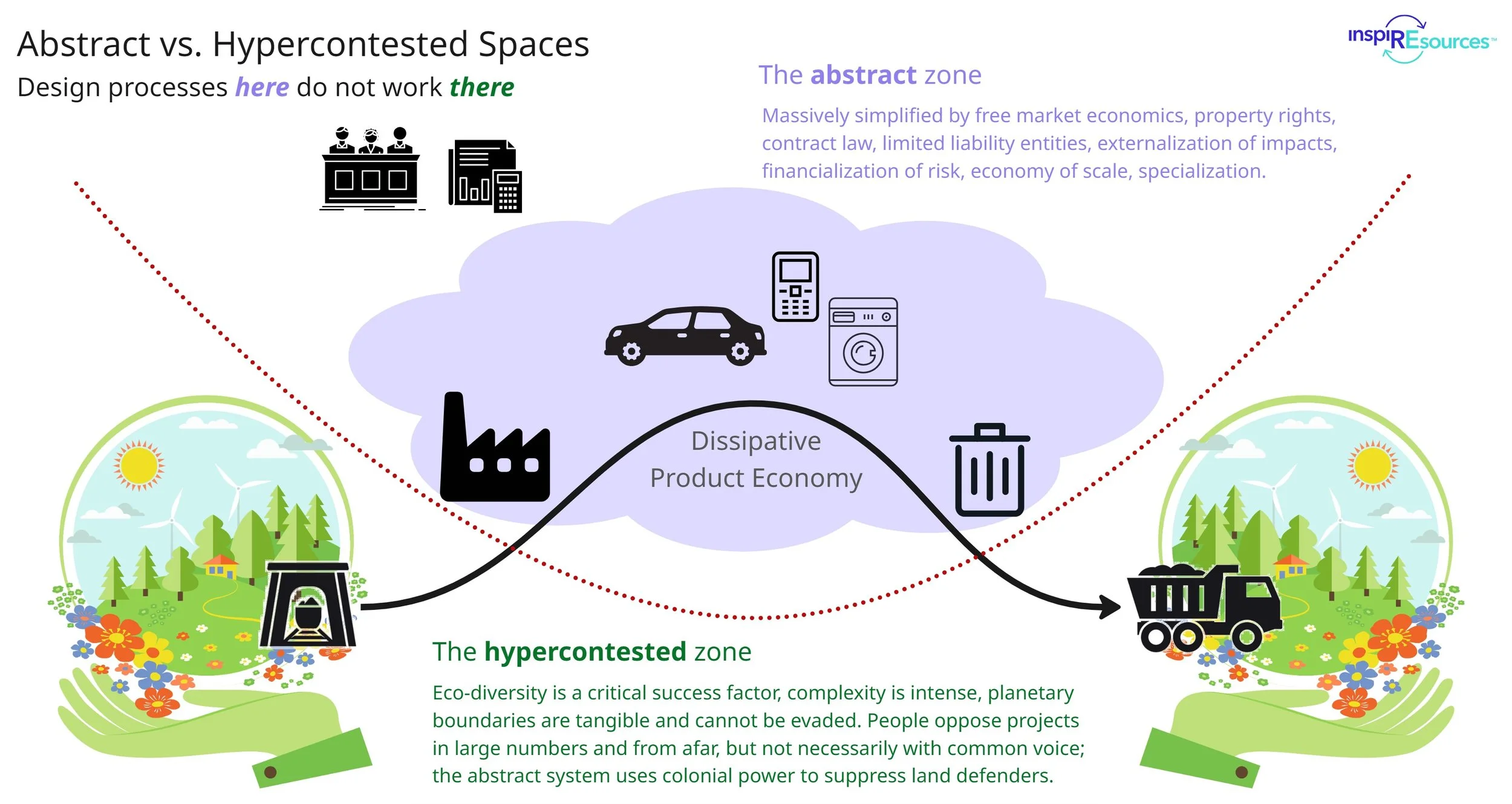

This might be hard to believe, but in ‘advanced’ economies we have created a simplified existence. With enforceable contracts, property rights, free market economics, limited liability corporations, insurance and credit, we have replaced ecosystem complexity with simple economic equations. Even if life sometimes seems complicated, it is shielded from complexity. We can act rationally as soulless consumers, seeking advantage without responsibility in linear value chains for products and services. We are rarely confounded or confused, unless perhaps we make the mistake of thinking about sustainability.

Where those linear value chains meet the Earth – at mines and landfills for example – it is harder to abstract away the complexity. Planetary boundaries are real. People who live and work at the interface with planetary systems know this: fishers, farmers, foresters and Indigenous people are only too aware that nature has the upper hand. They have developed a sophisticated resilience over thousands of years, on which we rely for our survival, and yet we suppress these people through colonial powers and mindsets. Why? Because they bring awkward complexity into our neatly ordered abstract world. They don’t fit our models.

The methods of suppression have changed over time as social progress has become wise to them. Violent force is still used sometimes to impose order, but it is no longer widely accepted as a prerogative of the nation state, let alone of the private capitalist. From a mining industry perspective, it is easy to imagine that we have reached a sunlit upland of community engagement and regulatory order – certainly many think that quite enough sacrifices have been made by project owners at the altar of environment, social and governance (ESG) correctness.

But control has not been shared. It has just evolved into meta-control.

The design process for mines is now tightly controlled by a technocratic elite of engineers, investors and regulators, all of whom are primarily acting to protect investors. Everyone else is on the outside, with perhaps a right to be consulted, but no guaranteed say in the framework of decision-making – the structure of what matters and in what proportions, and the creation of options. Even if you have the opportunity as a stakeholder to provide input, you don’t get to participate in trade-off decisions. This is why the term ‘stakeholder’ is derided by those with inherent rights to the land.

One might argue that transactional consultation is adequate power-sharing. But the judge of ‘adequate’ is not executive sentiment or even government policy: it is the absence of conflict and disruption on the ground. Mining companies cannot control popular sentiment, no matter how hard they try, and popular sentiment is highly attuned to injustice. Furthermore, expectations that fairness will be achieved, despite the complexity of competing claims, have been growing for centuries and will not be reversed.

Today this matters in Canada because we are going through a dramatic reassertion of national prerogative triggered by American hostility to our exports. The sudden desire to ‘get supply built’ is a strange reaction to loss of market demand, but responses to anxiety often are irrational in politics. The question here is not of motivation, but of execution: how can greater urgency of development be delivered while also continuing progress towards fairness, reconciliation and community wellbeing?

Inspire Resources has convened a small group of extremely insightful collaborators to re-imagine the design process for mines. We envision a co-design process, in which all parties can participate in decision-making in non-hierarchical spaces while retaining sovereignty over their own knowledge. The goal of the process is consensus, which is a higher bar than consent (especially if we adopt for consent Canada’s weak veto-less interpretation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, UNDRIP).

This will not be an easy path to follow, especially in these anxious times. It will require innovations in four domains:

There are no technically insurmountable obstacles in this diagram. Over time, with the right partners, we will develop a new prospectus for mining projects that will bring in new capital from non-traditional sources. It will be based not only on the product of mine design, but also critically on the process of consensus that enables development to proceed. Only by changing the social risk profile will we change the investors, which we must do because he/she who pays the piper calls the tune. It will be uncomfortable for incumbents, especially those on the inside of the power boundary, but we cannot let that stand in the way of progress.

Reversing the arrow of progress against injustice ‘in the national interest’ is not feasible: it will generate friction, leading to conflict and endless court challenge. These likely impacts are contrary to the national interest: they will benefit only foreign competitors (and lawyers). An alternative is not guaranteed to succeed, but we believe it should be tested at small scale, outside the glare of ‘major projects’. You will not see us on a conference stage any time soon – there is urgent work to be done.

As we have often said over the years, no company can effect system change alone. We are looking to participate in a collaborative effort, building open-source tools in small-scale ground-truth experiments; an essential counterbalance to the national-interest large-scale projects agenda. If this sounds like something you want to be a part of, please get in touch.